Brambles Holdings v Bathhurst City Council

Supreme Court of New South Wales, Court of Appeal

[2001] NSWCA 61; 53 NSWL 153

Case details

Court

Supreme Court (NSW)

Court of Appeal

Judges

Mason P

Heydon JA

Ipp A-JA

Outcome

Appeal dismissed

Appeal from

Hodgson CJ

Issues

Agreement

Application for special leave to appeal to the High Court of Australia denied.

Links

[2001] NSWCA 61 [Jade] ➤

Overview

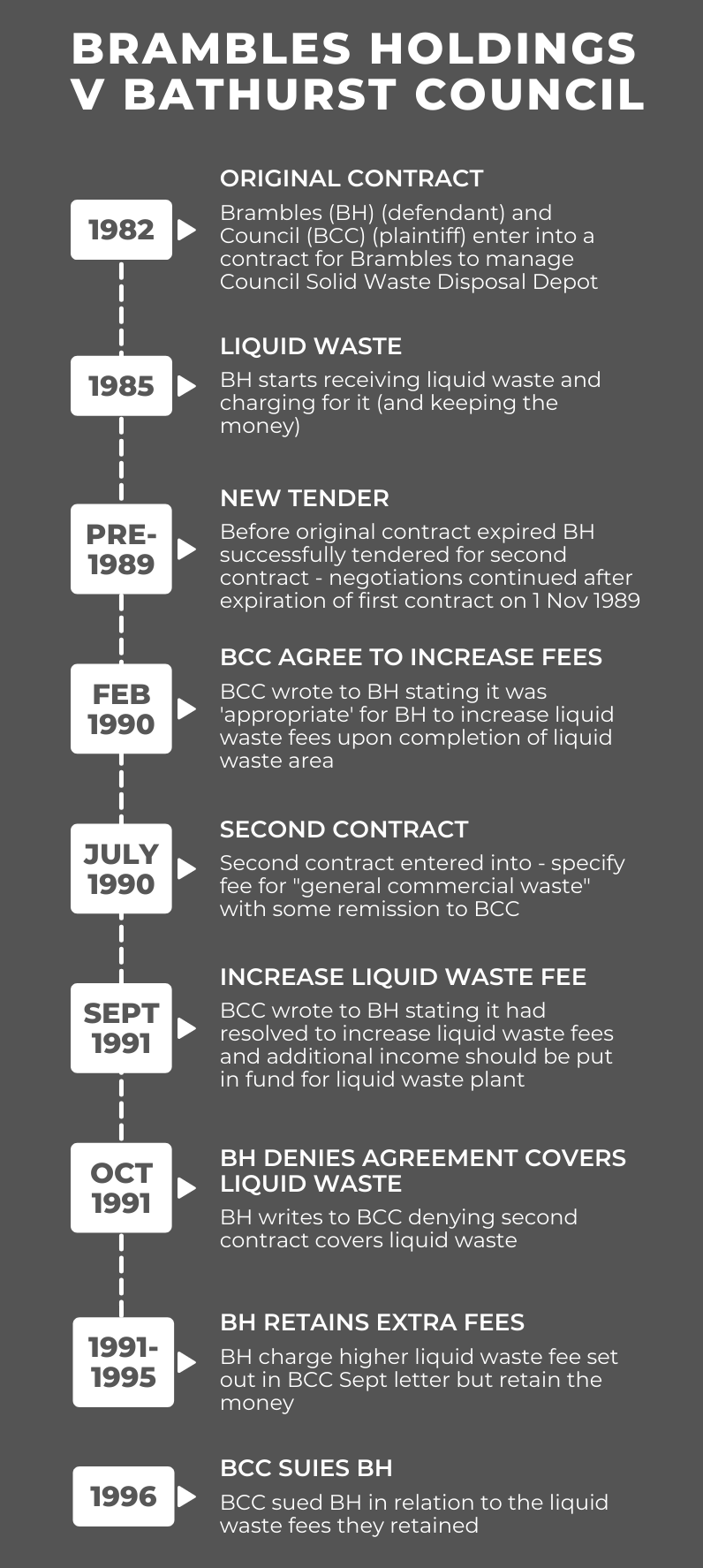

Brambles Holdings (defendant/appellant) (t/a Cleanaway) contracted with the Council (plaintiff/respondent) to manage their Solid Waste Disposal Depot.

After a few years Brambles started to receive liquid waste and charged for this waste.

Brambles subsequently tendered for a new contract and was successful; the resulting contract specified the fee to be charged for "general commercial waste", with a portion of that fee to be remitted to the Council.

Later, on 19 September 1991, Council wrote to Brambles stating it had decided to increase liquid waste fees. The additional fees were to be placed in a fund to establish a Liquid Waste Treatment Plant.

Brambles responded that it did not consider the contract between the parties covered liquid waste, but started charging at the higher fees proposed by Council; instead of remitting them it kept the fees.

Council subsequently sued Brambles to recover these fees.

The Court held that Council's letter of September 1991 constituted an offer with respect to the receipt of higher fees and their remission to Council and that this had not been rejected by Brambles by its October 1991 letter (or, per Heydon JA, if it had been rejected the offer nevertheless remained open for acceptance). That offer was accepted by conduct.

Importantly, as Council owned the facility, prices that could be charged were governed by Council. Brambles could not charge higher rates unless authorised to do so by Council. By raising its prices Brambles was acting consistently with Council's conditions for an increase in rates and this constituted acceptance by conduct.

Facts

[As the Trial Judge found them; set out from para 4 of the reasons of Heydon JA]

Brambles Holdings (defendant/appellant) (operating under the name "Cleanaway", contracted with the Council (plaintiff/respondent) to manage their Solid Waste Disposal Depot.

The Depot was a 'dry sanitary landfill tip' but Brambles began accepting liquid waste in about 1985, for which it charged a set fee based on volume. The fee was set by Council but retained by Brambles.

Brambles subsequently tendered for a new contract (for the period 1989-1996) and was successful; the resulting contract specified the fee to be charged for "general commercial waste", with a portion of that fee to be remitted to the Council.

While negotiations were proceeding on the new tender contract, Brambles increased the fee for accepting liquid waste. This led a customer to complain to Council. In response, Brambles wrote to Council in Jan 1990 advising of a revised price for liquid waste, including a lower price (of $15.00 per 500 gallons) for a six month period that would later increase to $25.

Council responded on 20 February 1990 that the proposed lower price was agreeable but the subsequent increase was 'difficult to substantiate' and requested Brambles reconsider the proposal. There was no apparent response.

On 12 July 1990 Council and Brambles entered a further four part contract. It included clauses 21 and 22 on collection of fees:

Clause 21: The Contractor shall be responsible for the collection of all fees and charges levied by the Council for refuse taken to the Depot, not being garbage, trade refuse or other wastes deposited at the depot for or on behalf of the Council in accordance with the following fees and charges. ... The Contractor shall be entitled to retain the fees and charges collected by him, other than the disposal fees specified in Clause 22. ...

[Amounts were set out for things like car tyres, truck tyres, animal carcass, compacted waste and 'general commercial waste. There was no separate line for liquid waste.]

Clause 22: Payment of fees to Council by Contractor

(a) Within one calendar month of the end of each quarter ... the contractor shall pay to council fees for disposal of compacted and uncompacted waste delivered to the Solid Waste Disposal Depot (hereinafter called ‘the disposal fees’). The disposal fees payable shall be: One dollar ($1.00) for each cubic metre of compacted waste, and - fifty cents ($0.50) for each cubic metre of uncompacted waste, ... all monies payable pursuant to this Clause shall be varied in accordance with the formula for review of fees set out in Clause 22b ...

In June 1991 Council wrote to Brambles stating the letter of 20 Feb incorrectly stated the quantity and that the true charge for liquid waste disposal was $15 per 1,000 gallons [not per 500 gallons]. Brambles' site manager thereafter telephoned Council to advise it was charging $15 per 1,000 gallons.

Council then considered increasing charges of liquid waste and on 19 September 1991 wrote to Brambles and said:

"At its meeting on 11 September 1991, Council resolved that:

(a) 'Liquid waste disposal costs be increased to 1.3 cents per litre from 1 October, 1991, and then quarterly by 1.0 cents per litre, up to a figure of 6.0 cents per litre and that the additional income be placed in reserve for the establishment of a Liquid Waste Treatment Plant.'

You are requested to charge these fees to Cleanaway, Mr Les Landers [the customer that had complained about the earlier increase] and all other depositors of liquid wastes at the Depot. Records could be kept, and dockets issued by you to Council each week, in a similar manner to the Disposal Fees being paid to Council for Solid Waste disposal.

...

Payment of all liquid waste disposal fees should be made to Council by Cleanaway each quarter in accordance with clause 22 of the Contract.'

On 3 October 1991 Brambles wrote to Council raising a number of concerns, including that id did not consider the contract between the parties covered liquid waste and requested extra tip fess for work involved in providing for liquid disposal:

... Our understanding is that the Bathurst Landfill Depot is presently licensed as a solid waste disposal depot, and as such, there is no licence for the disposal of liquid waste at the depot. Cleanaway recognises that the best place for liquid waste disposal is the current landfill depot, especially to stop illegal disposal and to minimise pollution. ...

... liquid waste disposal must be made economically viable for Cleanaway to perform the work required to dispose of the liquid in the best possible manner. Cleanaway must be adequately compensated for the work involved in digging and covering trenches. In February 1990, Council agreed to an increase in tip fees, but subsequently changed their mind in June 1991 and reduced the tip fees back to the old rates. The present rates do not make it viable to continue providing a liquid disposal service.

Cleanaway has no contract with Council for liquid disposal. The present contract is for the management of a solid waste disposal depot. In regard to the collection of a liquid waste levy on Council’s behalf, Cleanaway would make the point that this is not covered by the present contract.

... We would be appreciative if the above could be provided by Tuesday 15th October 1991 or we will need to review our options as regards acceptance of liquid into the landfill depot.

...

Later in October Brambles started collecting liquid waste fees at the rate set out in the September letter. It retained the fees rather than remitting them to Council.

Council discovered Brambles was charging the higher fees on 15 October 1991; despite this they did not 'request or demand payment of any part of the fees charged for liquid waste' (Ipp A-JA, para 132). This was explained in part by a Council officer who stated he considered the 19 September letter resulted in a separate liquid waste agreement from the July 1990 contract relating to solid waste.

Council subsequently sued Brambles to recover these fees.

One issue was whether the letter from Council regarding higher fees for liquid waste constituted an offer and, if it did, whether it had been rejected or accepted by Brambles. The Court held the letter from Council was an offer and that Brambles had accepted it by its conduct in charging the higher fees.

Trial Judge (Hodgson CJ)

The Trial Judge held that the 12 July 1990 agreement 'established fees for liquid waste, and prohibited the defendant from charging any other fees' so that Brambles was in breach of contract from 1 October 1991. [para 17 Heydon JA reasons]

The Trial Judge further held that the letter of 19 September 1991 was an offer. The offer was not accepted by Brambles' letter of 3 October, but was accepted by its conduct in charging the higher rates. [para 18 Heydon JA reasons]

"The terms of [the 19 Sept letter] were not accepted by the defendant's reply of 3rd October 1991 ... However, the defendant's charging for liquid waste at the rates specified in the letter of 19th September 1991 must be taken either as a breach of contract by the defendant, or the manifestation of acceptance of the terms of the letter of 15th September. On balance, I think that, considered objectively, it manifested acceptance of the terms, giving rise to a contract, provided there was consideration on both sides.

In my opinion, there was consideration provided by the Council to the defendant. The pre-existing authorisation of 1.1c was put on a firmer footing, under an arrangement in which there was plainly consideration going to the Council. Furthermore, it was dealing with a problem which was imposing burdens on the defendant, and thus assisting the defendant by providing some deterrent to excessive depositing of liquid waste.'

If there was no contract, Brambles would have been unjustly enriched by their conduct and obliged to return the fee charged less reasonable remuneration for its work [para 19 Heydon JA reasons]

Court of Appeal headnotes

Contract - Offer and acceptance - Whether letter constituted contractual offer to vary existing contract and create new contract between parties - Where language of offer ambiguous - Assessment of mutually known facts re contractual background and shared beliefs of parties - Whether conduct partially conforming to letter of offer constituted implied acceptance - Mutually understood purpose of offer - Whether response to offer was rejection of it - Whether response to offer merely constituted posturing and negotiation

Contract - Consideration - No immediate or guaranteed increase in earnings - likelihood of future increases in earnings

Contract - Construction of terms - Meaning of “General commercial refuse” - In context of agreement with local Council to operate waste depot - Meaning of “additional income” - In context of moneys required to be remitted to local Council from fees charged for receipt of liquid waste at waste depot

Remedies - Restitution - Doctrine of unjust enrichment - Discussion about controversy and debate in Australia surrounding development of doctrine and its applicability to claims in contract

Held (Court of Appeal)

Mason P

Agreed with Ipp AJA's reasons on the contractual change.

Noted the 'difficulties of pressing too far classical theory of contract formation based upon offer and acceptance'. [para 1]

Heydon JA

Briefly

Justice Heydon rejected the first ground of appeal (relating to the construction of the 12 July 1990 contract) then considered whether there was a contract brought about by the 19 September letter.

Justice Heydon held that the traditional method of determining agreement did not work well in this case. Here, the trial judge had found that the letter of 19 September was an offer (or at least, that absent pleadings on the question he could not reconsider that conclusion) and, although it was rejected by Brambles' offer of 3 October, circumstances suggested it remained open and capable of acceptance. Brambles accepted by their conduct in charging the higher prices set out in the 19 September letter.

On acceptance by conduct

The second ground of appeal argued that the trial judge erred in finding that there was a contract between the parties on the terms of the 19 Sept letter. They argued:

The 19 September letter was not an offer

If it was an offer then the 3 October letter was a rejection of the offer

If the 3 October letter was not a rejection, then the charging of higher fees and retaining them (without remission to Council) should be viewed as a rejection and not acceptance by conduct.

Even if there was an agreement it was not supported by consideration (it only permitted Brambles to keep the amount it was already entitled to keep).

In addition Brambles argued that if the contract prohibited Brambles charging fees for liquid waste (see ground 1, below), then charging and retaining fees would be a breach of contract, but Council did not claim there had been such a breach.

An offer?

His Honour appeared to have some sympathy for the view that the 19 Sept letter was not an offer, but observed that the matter was not pleaded nor argued below and therefore 'should not be entertained in this Court'

[52] There is much to be said for the view that the 19 September 1991 letter was not an offer, or cannot have been intended to affect legal relations by contract. That is because to some extent the letter does not take the form of proposing a particular course for examination by the defendant with a view to the defendant choosing between acceptance or rejection in the light of that examination. Rather it sets out a resolution permitting fees to rise, and then peremptorily requests the defendant to charge those fees. To that extent the letter uses the language of command. On the other hand, the letter is less peremptory in relation to the keeping of records and the issuing of dockets, and its concluding statement that payment should be made in accordance with cl 22 is suggestive of contractual dealing. This is because cl 22 did not permit an increase in fees beyond the indexation formula provided for, so that if the higher fees were to be payable under cl 22, the defendant's consent to a variation would be necessary.

Was the offer rejected by the 3 October letter?

Yes (at least in part). Held that on an objective construction -

[66] [t]he 3 October 1991 letter did not purport to terminate all negotiations with the Council and it invited further communications. But, in two respects, it rejected the assumptions or proposals contained in the 19 September 1991 letter ...

His Honour pointed to the references to viability of continuing to provide the liquid waste service and refusal to accept there was any existing contractual regime relating to liquid waste as evidence of Brambles rejecting aspects of the 19 September letter. To this extent the 3 Oct 1991 letter was a rejection of the 19 September offer.

If it was rejected does that prevent it forming the basis of a contract as a result of the offer and subsequent conduct?

Brambles argued that the rejection meant that the offer ceased and could not thereafter be accepted by conduct.

His Honour criticised the need - always - to conform to a strict 'offer and acceptance' analysis:

[68] According to the defendant, the effect of the rejection of the 19 September 1991 offer was that it ceased to have operative effect unless it was later revived in some way, and it was not. Hence it was not capable of being accepted by conduct.

...

[71] The defendant's contention that the rejection of the Council's offer meant that it was no longer capable of acceptance by conduct, and its related contention that its conduct did not constitute acceptance, depend heavily on the view that offer and acceptance analysis must invariably be employed in reaching decisions about the formation of contracts. While the process by which many contracts are arrived at is reducible to an analysis turning on the making of an offer, the rejection of the offer by a counter-offer and so on until the last counter-offer is accepted, that analysis is neither sufficient to explain all cases nor necessary to explain all cases. Offer and acceptance analysis does not work well in various circumstances. One example is a contract for the transportation of passengers on mass public transport (MacRobertson Miller Airline Services v Commissioner of State Taxation (Western Australia) (1975) 133 CLR 125 at 136–140). Another is the contract between competitors in a regatta: though they did not communicate with each other but only with the organiser of the regatta, they are bound by their conduct in “entering for the race, and undertaking to be bound by [the] rules to the knowledge of each other” (Clarke v Earl of Dunraven [1897] AC 59 at 63). ... Another example concerns the exchanges of contracts to sell land, which are hard to analyse in offer and acceptance terms; despite that Lord Greene MR observed of the practice: “Parties become bound by contract when, and in the manner in which, they intend and contemplate becoming bound. That is a question of the facts of each case …” (Eccles v Bryant and Pollock [1948] Ch 93 at 104). Another example concerns simultaneous manifestations of consent .... Another example concerns contracts between numerous parties, or even two parties, negotiated at meetings but not assented to until each party executes counter parts. Another is where the contract is made through a single broker acting for both parties. Another is where the parties are deadlocked and they agree to submit to a solution reached by a third party.

[72] In New Zealand Shipping Co Ltd v A M Satterthwaite & Co Ltd [1975] AC 154 at 167, Lord Wilberforce, in delivering the majority advice of the Privy Council about a bargain evidenced by a bill of lading between a shipper and a stevedore made through a carrier as agent, said:

"… It is only the precise analysis of this complex of relations into the classical offer and acceptance, with identifiable consideration, that seems to present difficulty, but this same difficulty exists in many situations of daily life, eg, sales at auction; supermarket purchases; boarding an omnibus; purchasing a train ticket; tenders for the supply of goods; offers of rewards; acceptance by post; warranties of authority by agents; manufacturers' [sic] guarantees; gratuitous bailments; bankers' commercial credits. These are all examples which show that English law, having committed itself to a rather technical and schematic doctrine of contract, in application takes a practical approach, often at the cost of forcing the facts to fit uneasily into the marked slots of offer, acceptance and consideration."

[73] Anson's Law of Contract, 27th ed, (J Beatson), (1998) Oxford, Oxford University Press, at 28 concludes:

"… It would be a mistake to think that all contracts can thus be analysed into the form of offer and acceptance or that, in determining whether an exchange does give rise to a contract, the sole issue is whether the communications match and are identical. The analysis is, however, a working method which, more often than not, enables us, in a doubtful case, to ascertain whether a contract has in truth been concluded, and as such may usefully be retained." (footnote omitted)

[74] Thus offer and acceptance analysis is a useful tool in most circumstances, and indeed is “normal” and “conventional” (Gibson v Manchester City Council [1979] .... But limited recognition has been given to the possibility of finding that contracts exist even though it is not easy to locate an offer or acceptance. In Integrated Computer Services Pty Ltd v Digital Equipment Corp (Aust) Pty Ltd (1988) ... McHugh JA (Hope JA and Mahoney JA concurring) said:

"It is often difficult to fit a commercial arrangement into the common lawyers' analysis of a contractual arrangement. Commercial discussions are often too unrefined to fit easily into the slots of ‘offer’, ‘acceptance’, ‘consideration’ and ‘intention to create a legal relationship’ which are the benchmarks of the contract of classical theory. In classical theory, the typical contract is a bilateral one and consists of an exchange of promises by means of an offer and its acceptance together with an intention to create a binding legal relationship … Moreover, in an ongoing relationship, it is not always easy to point to the precise moment when the legal criteria of a contract have been fulfilled. Agreements concerning terms and conditions which might be too uncertain or too illusory to enforce at a particular time in the relationship may by reason of the parties' subsequent conduct become sufficiently specific to give rise to legal rights and duties. In a dynamic commercial relationship new terms will be added or will supersede older terms. It is necessary therefore to look at the whole relationship and not only at what was said and done when the relationship was first formed."

Justice Heydon referred to a number of other examples, including Empirnall holdings, where McHugh held that:

"... where an offeree with a reasonable opportunity to reject the offer of goods or services takes the benefit of them under circumstances which indicate that they were to be paid for in accordance with the offer, it is open to the tribunal of fact to hold that the offer was accepted according to its terms."

Based on a review of these decisions Justice Heydon stated:

[80] If offer and acceptance analysis is not always necessary or sufficient, principles such as the general principle that a rejection of an offer brings it to an end cannot be universal. A rejected offer could remain operative if it were repeated, or otherwise revived, or if in the circumstances it should for some other reason be treated, despite its rejection, as remaining on foot, available for acceptance, or for adoption as the basis of mutual assent manifested by conduct. [emphasis added]

In this case, although Brambles originally rejected the offer, it 'soon take advantage of the benefit' of the offer which could convey either that it was acting in breach of condition or was accepting that condition; a reasonable person would consider it to be the latter (para 82). In addition, although the original offer had been rejected, there was 'an element of permanence' in the offer (para 84) and Brambles 'must have assumed that the resolution was still operative because it began to increase fees ...' Further, it did not matter that this 'acceptance' was not communicated: as long as Council knew of the acceptance (in this case by becoming aware Brambles was charging the higher fee) there was a contract, even if notice of the conduct was not brought to the attention of Council by Brambles directly (para 86).

Was there consideration?

Justice Heydon held that there was consideration because prior to the agreement based on the 19 Sept letter there was no contractual entitlement for Brambles to retain any portion of the fee collected for liquid waste (even though in practice they had been doing this). The agreement provided for a contractual entitlement to retain a portion of the fee which was capable of amounting to consideration.

In addition, the collection of higher fees for the purpose of establishing a new plant would be of benefit to Brambles in reducing the existing burden associated with the collection of liquid waste.

On whether the 12 July 1990 contract prohibited Brambles from charging fees for liquid waste

The first ground of appeal was that the TJ erred in holding liquid waste fell within clause 21 (with the result Brambles would be barred from charging fees not approved by Council). This was relevant for a number of reasons, including the impact it would have on a finding of 'consideration' for the September contract.

Justice Heydon discussed principles relating to implication of terms"

[24] The first relevant principle of law is that pre-contractual conduct is only

admissible on questions of construction if the contract is ambiguous and if the

pre-contractual conduct casts light on the genesis of the contract, its objective

aim, or the meaning of any descriptive term: Codelfa ...[25] The second relevant principle is that post-contractual conduct is admissible

on the question of whether a contract was formed: Howard Smith...[26] The third relevant principle is that post-contractual conduct is not admissible

on the question of what a contract means as distinct from the question of

whether it was formed. ...[27] The fourth relevant principle is that the construction of a contract is an

objective question for the court, and the subjective beliefs of the parties are

generally irrelevant in the absence of any argument that a decree of

rectification should be ordered or an estoppel by convention found. No

argument of these kinds was advanced in this case.[28] The fifth relevant principle is that terms may be implied in one of four ways. ... [quoting Hodgson J in Carlton & United Breweries Ltd v Tooth & Co Ltd

(i) Implications contained in the express words of the contract ...

(ii) Implications from the "nature of the contract itself" as expressed in the words of the contract ...

(iii) Implications from usage (for example, mercantile contracts)

(iv) Implications from considerations of business efficacy...]

Justice Heydon held that the reasoning of the trial judge 'conformed to these principles' and went on to discuss this further, finding that the trial judge's conclusions about the 12 July 1990 contract were correct [para 46].

Ipp A-JA

In brief

Justice Ipp adopted a more traditional offer-acceptance approach. Considering the circumstances (including beliefs of the parties) leading up to the 19 September letter, his Honour held that it was an offer that, if accepted, would give rise to a separate contract dealing with the determination of fees and remission to Council.

Brambles' 3 October letter was not a rejection - it included a statement of common understanding (that there was no existing contract with the Council for liquid waste disposal) and 'posturing' regarding the adequacy of rates, but the expression of dissatisfaction with the offer was not the same as a rejection.

Brambles' conduct in charging higher fees was 'unequivocal acceptance of the offer'; in particular, as the terms of the offer were indivisible, accepting the benefits of the offer was the same as accepting the offer 'in accordance with its terms' (para 173).

Further, there was consideration; the offer provided for the establishment of a waste treatment plant that would be in Brambles' interests and, in addition, it meant Brambles could continue to use Council's land for liquid waste disposal without the risk of the Council limiting the volume of such waste (para 175). This was adequate consideration.

Detail

Justice Ipp adopted a more traditional approach, beginning with a helpful succinct overview of the claim.

His Honour first accepted that the July 1990 contract governed the charging for liquid waste (agreeing with the reasons of Justice Heydon on that point).

Was the 19 September 1991 letter an offer?

For the reasons explained by Justice Heydon it needed to be treated as an offer (it wasn't pleaded)

Was the offer accepted?

Yes - but for different reasons than Justice Heydon.

The trial judge held that at the relevant time there was a 'non-contractual' arrangement by which Brambles could charge for liquid waste in accordance with the fees set out in the 20 Feb 1990 letter. Justice Ipp considered that the letter of 20 Feb 1990 was a contractual offer accepted by conduct.

Justice Ipp noted that the new contract on July 1990 altered terms relating to collection of fees and indexing. He agreed with Heydon JA that:

[118] I agree with Heydon JA, for the reasons set out by him, that the fees for

general commercial waste under cl 21 were fees for liquid waste which the

appellant was entitled to charge and retain, and I agree that the effect of cl 21

was to prohibit the appellant from charging any fees for liquid waste other than

those set out for general commercial waste in that clause. As will be seen,

however, this does not appear to have been the view of the July 1990 contract

that was taken by the parties.

Justice Ipp noted that from October 1991 Brambles charged fees as set out in the 19 September letter, but did not keep records or issue dockets to Council or pay disposal fees to Council.

When assessing whether the 19 September 1991 offer was accepted, Justice Ipp noted it was 'necessary to determine, precisely, the terms of that offer' (para 138). His Honour noted that where there are ambiguities, evidence of surrounding circumstances is admissible 'for purposes of construing the contract'. There were ambiguities here so regard could be held to common assumptions (para 141). His Honour then went through the extrinsic material.

His Honour noted (as had Heydon JA) that 'the parties (wrongly ...) believed that the July 1990 contract, while governing the receipt of liquid waste, did not regulate the charging of fees for liquid wastes' (para 147), but Brambles did accept that Council had a right to determine the fees for liquid waste.

When considered in this context Ipp A-JA held that the 19 Sept 1991 letter was 'written on the assumption that, upon acceptance, it would give rise to a contract that dealt separately and independently with the determination of fees for liquid waste and the payment of part of them by the appellant to the Council. The parties did not believe that the July 1990 contract applied to liquid waste ...' (para 151)

On the question of whether it was rejected by Brambles' letter of 3 October, Ipp A-JA held that the statement that they had 'no contract with Council for liquid disposal' was not a rejection of the offer; Council had not claimed that such a contract existed (para 155). Further, the statement in the 3 October letter 'that "the present rates do not make it viable to continue providing a liquid disposal service" was not a rejection of the offer' (para 156). This was 'merely part of the posturing that often accompanies negotiation'.

His Honour concluded that while the 3 October letter 'expressed dissatisfaction' with the offer it did not amount to a rejection (para 158).

On the question of whether the offer was accepted by Brambles, Ipp A-JA held that there was acceptance by conduct. He rejected the claim made by Brambles that, by increasing fees but not complying with other conditions, there was no unqualified acceptance of the offer. In particular, his Honour noted that both parties believed the fees could not be increased without the consent of Council and it was understood additional fees were to be used to construct a liquid waste treatment plant. Given this context, 'the fact that the appellant charged the higher fees is conclusive evidence that it agreed to all the conditions contained in the offer of 19 September 1991' (emphasis added; para 173). The offer was indivisible, so objectively viewed, charging the higher fees constituted acceptance (para 173).

Was there consideration?

Yes. The offer provided for the establishment of a waste treatment plant that would be in Brambles' interests and, in addition, it meant Brambles could continue to use Council's land for liquid waste disposal without the risk of the Council limiting the volume of such waste (para 175). This was adequate consideration.